Raising Chickens for Meat: The Mise en Place of Humane Slaughter

Having a well-laid plan in place for your meat birds’ final day is as important to humane treatment as preparing for the arrival of spring chicks.

Spring days bring baby chicks. Farmers in my town are ordering their birds. Feed stores are stocking the real-life peeps, as opposed to the marshmallow versions (though maybe they’re stocking those, too). Be they egg-layers or meat birds, those little live chicks are hard to resist, they’re so darn cute.

But for folks who are interested in becoming more self-reliant as backyard growers, this is the time when we start looking ahead and dreaming and then scheming, calculating our freezer volume to frozen-bird capacity and planning how to pull it all off.

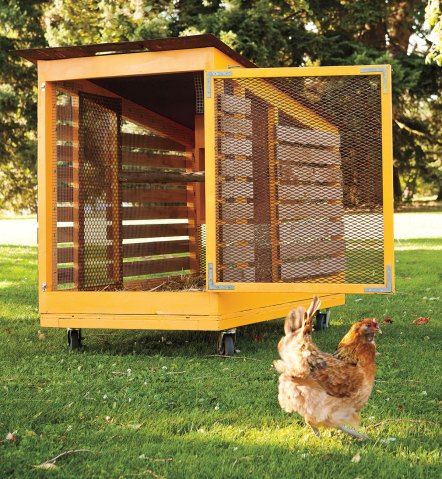

Backyard growers may very well become the next small-scale poultry farmer. My friend and colleague Jefferson Munroe of The Good Farm in Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts, has been known to say that without access to humane, small-scale, local, and permitted slaughter via a mobile poultry processing unit (like the one pictured below), he wouldn’t have become a chicken farmer. Access is what enabled him to go from being a backyard grower to raising enough meat birds that now chicken is the foundation of his business. Jefferson scaled up from micro to mini, when up to the scale of our industrial food system. Mini means that now there are roughly 10,000 more local chickens for sale through farmers’ markets, grocers, restaurants, and even public schools. All this is dependent on the ability to provide chickens with a humane last day.

https://www.instagram.com/p/cNkhgTLFcI“Have an exit strategy,” Elizabeth Packer likes to tell to people raising chickens. She’s a farmer and the owner of Smith Bodfish & Swift feed store in Vineyard Haven. On the the wall calendar in her office, she’s got the word “Chicks” written in bold pink ink on every upcoming Wednesday for the next five or six weeks. It’s a reminder to her and, most importantly, to her customers that spring is not just about getting the birds. It’s about the inevitable day to come, eight to ten weeks down the road. She also likes to say, “there are ‘no rescues’ in broiler world.” These birds are meant to go, and go they must. So having a responsible and doable plan in place for that deadline is crucial.

Slaughter days ought to be the calmest days around. And they can be. If you’ve never done a slaughter before, I encourage you to visit an experienced farmer or neighbor. Take notes, ask questions. Then go back and look at how to set up on your place. Evaluate the lay of your land, including nearby sources for potable water, hot and cold water access, electricity, compost, containers, ice, and freezer space. And look for the helpers. Bring them in. Slaughter days are not solos. Train the helpers, if need be, and afterwards, in gratitude, feed them well.

Think of butchering day in terms of the French culinary phrase mise en place, meaning “everything in its place.” It’s a philosophy, an approach, and a strategy for chefs to be prepared. As a home cook, I think of mise en place as advice as well as an admonition. I’ve had a great many failures when I’ve rushed and didn’t do my advance prep, or neglected to read a recipe through to the end. I hate the hindsight of “if only I had…”.

In the end, this is about good, clean, humanely raised and humanely slaughtered chicken for our tables. Having everything in place for that last day at around the same day your new broiler flock starts scratching and pecking on your grass means you’ve got mise en place. It’s only afterwards that you really get to start cooking.